Exploring Object Layouts

Background

The yearly “Performance improvements in .NET” blog post is always a treasure trove of low-level knowledge on performance. This latest edition had several examples of significant improvements as a result of allocating smaller objects, rather than allocating less frequently. Of course no allocations are even better but at the same time allocations are part of life so they are unavoidable to some degree.

Take PR #81251 for example: by replacing a couple of fields with a well-known value on an existing int field, we can reduce the overall size of each object. After a bit of browsing I spotted a similar pattern in Ping where it seemed I would be able to apply the same idea: bool _canceled and bool _disposeRequested could just as easily be flags for the existing int _status field. The _status field only supports a few values right now so we can easily tack more on.

After a bit of playing around to figure out how to build the runtime locally and run a comparison benchmark, I ended up with this PR: https://github.com/dotnet/runtime/pull/94151. Lo and behold, BenchmarkDotNet claims we allocated the same amount after my changes. How is that possible when it literally stores less data?

Diagnosis

At first I looked at the issue through WinDbg. To make things easy for ourselves we’ll create two class definitions with the fields of the Ping class with and without the two booleans:

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Net.NetworkInformation;

using System.Diagnostics;

var a = new Ping();

var b = new Ping2();

Debugger.Break();

public partial class Ping : Component

{

private readonly ManualResetEventSlim _lockObject = new ManualResetEventSlim(initialState: true); // doubles as the ability to wait on the current operation

private SendOrPostCallback? _onPingCompletedDelegate;

private bool _disposeRequested;

private byte[]? _defaultSendBuffer;

private CancellationTokenSource? _timeoutOrCancellationSource;

private bool _canceled;

private int _status = 0;

public event PingCompletedEventHandler? PingCompleted;

}

public partial class Ping2 : Component

{

private readonly ManualResetEventSlim _lockObject = new ManualResetEventSlim(initialState: true); // doubles as the ability to wait on the current operation

private SendOrPostCallback? _onPingCompletedDelegate;

private byte[]? _defaultSendBuffer;

private CancellationTokenSource? _timeoutOrCancellationSource;

private int _status = 0;

public event PingCompletedEventHandler? PingCompleted;

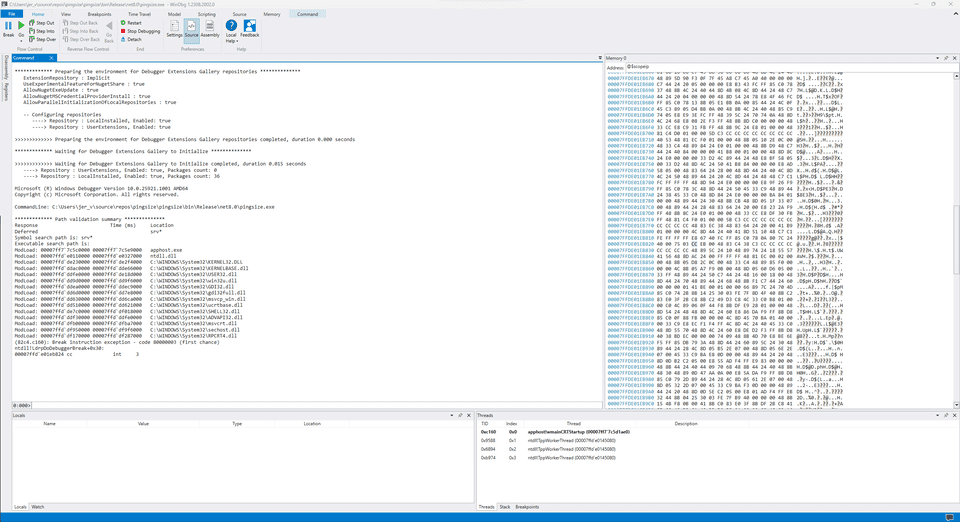

}Compile this in release mode (dotnet build -c Release) and load the .exe in WinDbg, you’ll see something along these lines:

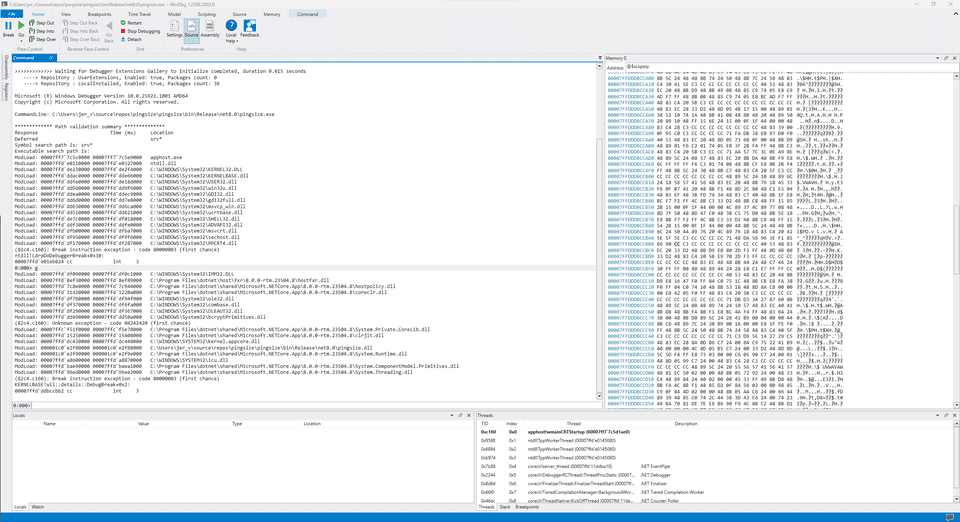

Next, run the program so it hits the breakpoint we set via Debugger.Break():

gAt this point we can look for our previously-created Ping objects with something like this:

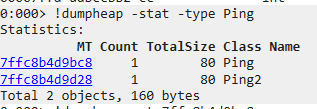

!dumpheap -stat -type PingImmediately we can see that both Ping and Ping2 have one instance each. Crucially, both show up as having a total size of 80 bytes. This aligns with our BenchmarkDotNet findings that no allocation reduction was realised.

To investigate deeper we can click on the link for the 7ffc8b4d9bc8 Method Table which will execute !dumpheap -mt 7ffc8b4d9bc8. This then tell us that the memory address for that object is located at 2258d00a648.

Clicking that link then executes !dumpobj /d 2258d00a648 which gives us this nice overview of the object:

0:000> !dumpobj /d 2258d00a648

Name: Ping

MethodTable: 00007ffc8b4d9bc8

EEClass: 00007ffc8b4e33f8

Tracked Type: false

Size: 80(0x50) bytes

File: C:\Users\jer_v\source\repos\pingsize\pingsize\bin\Release\net8.0\pingsize.dll

Fields:

MT Field Offset Type VT Attr Value Name

0000000000000000 4000019 8 ...ponentModel.ISite 0 instance 0000000000000000 _site

0000000000000000 400001a 10 ....EventHandlerList 0 instance 0000000000000000 _events

00007ffc8b355fa0 4000018 98 System.Object 0 static 0000000000000000 s_eventDisposed

00007ffc8b4daa90 4000001 18 ...ualResetEventSlim 0 instance 000002258d00a698 _lockObject

00007ffc8b3992d0 4000002 20 System.Void 0 instance 0000000000000000 _onPingCompletedDelegate

00007ffc8b35d068 4000003 44 System.Boolean 1 instance 0 _disposeRequested

0000000000000000 4000004 28 SZARRAY 0 instance 0000000000000000 _defaultSendBuffer

00007ffc8b3992d0 4000005 30 System.Void 0 instance 0000000000000000 _timeoutOrCancellationSource

00007ffc8b35d068 4000006 45 System.Boolean 1 instance 0 _canceled

00007ffc8b391188 4000007 40 System.Int32 1 instance 0 _status

00007ffc8b3992d0 4000008 38 System.Void 0 instance 0000000000000000 PingCompletedExcellent! Now we see the exact layout of our fields in the object. Worth noting here that the object is 80 bytes — in decimal. In hexadecimal, that corresponds to 0x50. This is particularly relevant because the Offset column specifies its values in hexadecimal as well.

Note that the CLR chooses the most optimal layout for us. We can override this behaviour in structs so beware when using LayoutKind.Sequential!

Object Layout

At this point we’ll take a step back and revise some CLR fundamentals: what does an object look like? For simplicity we’ll focus on 64-bit systems here. That means we can assume references are 8 bytes and objects (as a whole) are padded to an 8-byte boundary. Furthermore, every object contains two references by default: the Object Header and a reference to the Method Table. Both are 8 bytes so we know that the resulting object will be at least 16 bytes in size before we’ve even started counting our fields.

Interestingly, the Object Header is actually defined with a negative offset (i.e.

-8 bytes). So our actual object at offset0is the Method Table reference.

With this knowledge in mind we can now use the offsets in the above output to show how the object is laid out. To simplify our life, we write a small console script to help with translating hexadecimal to decimal:

for (var i = 0; i < 100; i+= 8)

{

Console.WriteLine($"{i}: {i:x}");

}

Console.Read();This outputs:

0: 0

8: 8

16: 10

24: 18

32: 20

40: 28

48: 30

56: 38

64: 40

72: 48

80: 50

88: 58

96: 60Armed with this information we can deduce the following object layout:

Field Offset (hex) Offset (dec) Size (bytes)

<Object Header> -0x08 -8 8

<Method Table Pointer> 0x00 0 8

_site 0x08 8 8

_events 0x10 16 8

_lockObject 0x18 24 8

_onPingCompletedDelegate 0x20 32 8

_defaultSendBuffer 0x28 40 8

_timeoutOrCancellationSource 0x30 48 8

PingCompleted 0x38 56 8

_status 0x40 64 4

_disposeRequested 0x44 68 1

_canceled 0x45 69 1Object sizes

References are 8 bytes, but

intis a 32-bit integer (i.e. four bytes) while booleans are defined as a single byte.

This gives us a total range of -0x08 to 0x46, which equates to 0x4e or 78 bytes. What gives?

Remember the Object Layout section from above:

(..) are padded to an 8-byte boundary

78 is not a multiple of 8 so we need to add padding for that. Specifically, we need to add two bytes worth of padding (rounding up to the nearest multiple) so our object actually becomes

Field Offset (hex) Offset (dec) Size (bytes)

<Object Header> -0x08 -8 8

<Method Table Pointer> 0x00 0 8

_site 0x08 8 8

_events 0x10 16 8

_lockObject 0x18 24 8

_onPingCompletedDelegate 0x20 32 8

_defaultSendBuffer 0x28 40 8

_timeoutOrCancellationSource 0x30 48 8

PingCompleted 0x38 56 8

_status 0x40 64 4

_disposeRequested 0x44 68 1

_canceled 0x45 69 1

<Padding> 0x46 70 2This now gives us a valid object of 80 bytes. It also immediately makes it clear why our optimisation didn’t work: if you remove _disposeRequested and _canceled from the object definition then we end up with 76 bytes which is also not a multiple of 8. As a result, the CLR will introduce four bytes of padding and end up with an 80-byte object once again.

Simplified Diagnosis

Spelunking through WinDbg is certainly not trivial! Fortunately, there are projects out there that will help us a long way here. Using the ObjectLayoutInspector we can inspect the object size at runtime and print out a helpful overview. Add a reference to its NuGet package (<PackageReference Include="ObjectLayoutInspector" Version="0.1.4" />) and add the following to our application:

ObjectLayoutInspector.TypeLayout.PrintLayout<Ping>();Run the console application and we can see the following output:

Type layout for 'Ping'

Size: 64 bytes. Paddings: 2 bytes (%3 of empty space)

|=======================================================================|

| Object Header (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Method Table Ptr (8 bytes) |

|=======================================================================|

| 0-7: ISite _site (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 8-15: EventHandlerList _events (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 16-23: ManualResetEventSlim _lockObject (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 24-31: SendOrPostCallback _onPingCompletedDelegate (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 32-39: Byte[] _defaultSendBuffer (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 40-47: CancellationTokenSource _timeoutOrCancellationSource (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 48-55: PingCompletedEventHandler PingCompleted (8 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 56-59: Int32 _status (4 bytes) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 60: Boolean _disposeRequested (1 byte) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 61: Boolean _canceled (1 byte) |

|-----------------------------------------------------------------------|

| 62-63: padding (2 bytes) |

|=======================================================================|This confirms our WinDbg findings: padding is applied to the end of the object and we’re seeing 16 bytes of overhead.

Conclusion

In this case, padding is inevitable. Even if we were to replace the int _status with a byte _status, we’d still use a single byte on top of the previous boundary and thus incur seven bytes of padding. As a result, moving these fields into the status enum will gain no benefit from an object size perspective.

This type of optimization shows most promise when used in a type that has multiple fields smaller than the pointer size — we only see effects if we’re able to go down to a lower multiple of our byte boundary. Of course, removing a reference field entirely will always yield results!